Demography, Dividends, and How Millennials Will Save National Spacepower

Have you ever noticed that there are few space policy wonks, strategists, and boffins between the ages of 45 and 60? I have. Read and find out why!

Have you ever noticed that there are very few space policy wonks, space strategists, and space boffins between the ages of 45 and 60? I have. It was painfully obvious when I joined the space industry in 2003. Looking at the government, industry, and academic landscape now, it's clear that we have several challenges ahead.

Demographics and the Peace Dividend have conspired to hamper the human capital contribution to national spacepower. Generation X is deeply underrepresented in the space workforce, and for 10-15 years this will be felt in reduced numbers of senior space workforce members and experienced leaders. However, Millennials and Generation Z are entering the space workforce in droves, giving much promise to future United States National Spacepower.

To unwrap this wet paper bag we'll need to look at 1) demography of national populations, 2) the collapse of the Soviet Union and the resulting Peace Dividend, and 3) understand how these two historical events have combined to give us today's human capital challenges in national spacepower.

Huzzah!

1) Demography

No, not Demogorgon (yes, that's a Stranger Things reference). I'm talking about how populations are composed and change over time.

The first insight into our lack of senior space professionals has to do with the glacial but very deterministic progression of people through their life stages. I'll discuss how those populations and their compositions impact spacepower through their raw human capital.

This analysis is focused on United States Spacepower, so I'll only look closely at United States demographics. Glancing at European and Chinese demographics, its unclear the same story unfolded as in the United States.

I'll also state that the future does not look as rosy for future European and Chinese space workforces and human capital. Both of their demographics have peaked and are in net decline as of this year. Said differently, their available raw human capital will decrease for the foreseeable future. This will affect their spacepower.

Raw Human Capital as a Resource

The oft-quoted maxim below summarizes a favorite view of demography with extreme parsimony:

"Demography is Destiny." (Auguste Comte, French Philosopher, 1798-1857)

If we're looking for a dearth of 45-60 year-olds, we can start with how many individuals were born 45-60 years ago.

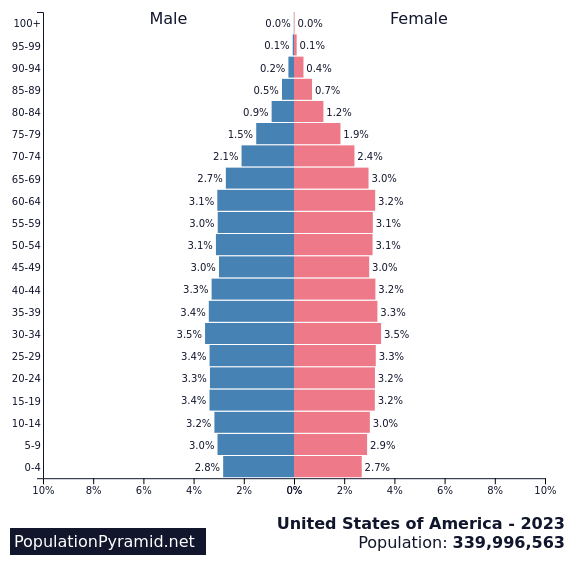

If you squint, you can see a 'neck' in the population period with those aged 43-58. The Baby Boomer generation are entering mass retirement and their end-of-life stages, so the 'neck' is much less visible now than it was in the past. Scroll down for the same figure in 1993.

The Revenge of Generation X

Folks aged 43-58 (born 1965-1980) are called Generation X. They had the pleasure of growing up with MTV, massive inflation, and the end of the Cold War.

At their births, there are vastly fewer Generation X individuals (55M) than Baby Boomers (76M). While the 'Boomer' and 'Gen-X' periods were of different lengths (18 years compared to 15 years), accounting for this difference still yields a 4.2M/yr 3.7M/yr annual births, respectively. Generation X had ~12% fewer annual births than the Baby Boomer generation.

What does that mean for national spacepower? It means there are fewer senior space professionals now than there were 10-15 years ago, even if rates of employment in the space industry had remained constant for Generation X.

They didn't.

2) A Unipolar World and The Bounty of the Peace Dividend

Before I dig into this topic, I have a brief note.

I found this section difficult to write. Not for lack of any ideas, but because much of the evidence is circumstantial and anecdotal. Budget changes and undergraduate enrollments are easy enough to find, but actually understanding how large the Generation X workforce was and where individuals focused their careers is very difficult. I'm an engineer more used to first principles and laws of motion; social sciences are foreign to me and I claim no relevant skill. However, I think this topic is ripe for #datascience!

Below I'll present a sketch of what I understand to have happened.

What is the Peace Dividend?

In 1991 on December 26, the United Soviet Socialist Republic (USSR) flag was lowered at the Kremlin.

This heralded the end of the Cold War. This meant peace in our time. The immediate threat of nuclear holocaust had passed. The world became unipolar. We had reached The End of History. We look back on this time with different perceptions, but that's how it felt at the time.

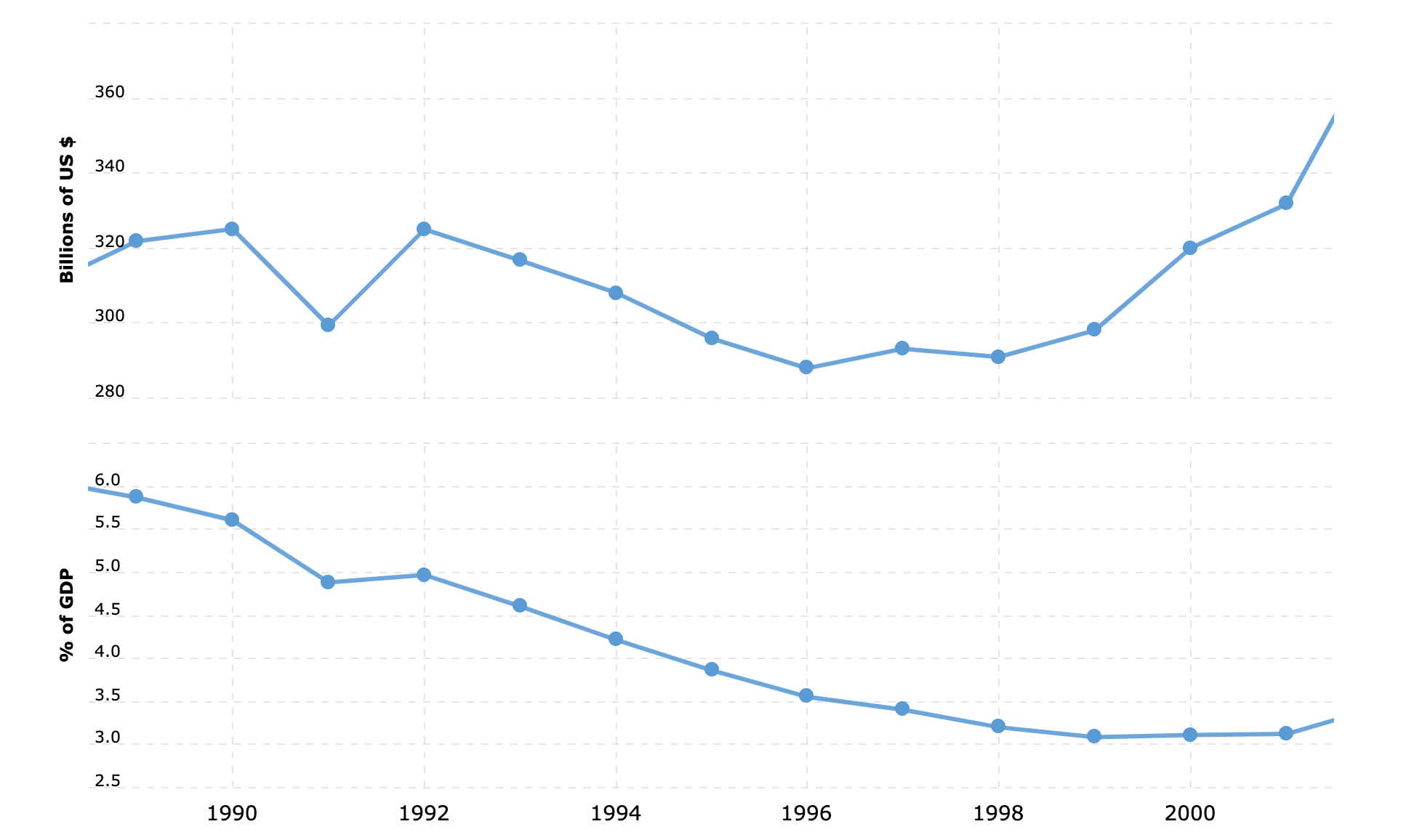

The Peace Dividend, a term credited to President George Bush (the Elder), is the bounty that the United States expected to reap because it no longer had to dedicate massive factions of its economy to defense. It shows up clearly in defense spending (see below) during those years.

The absolute dip doesn't seem like much - perhaps 10% over 5 years. At the same time that defense spending dropped from 6% to 3% of the economy, remember that the population and economy was increasing at a strong clip. Further, when a government entity absorbs a 10% absolute cut, they prioritize their existing workforce and facilities. That means new young employees are not hired. Research & development funding is cut because it's not required for daily operations. Academics research other things because funding isn't available. Industry focuses on maintaining existing programs of record.

Besides, if you're the only global superpower and there are zero great power contenders (as in the 90s), what are you developing? What new space systems do you need to research and claw out of your imagination when faced with The End of History?

Growing up with a father that worked in the aerospace industry I can personally attest to the layoffs and displacement in aerospace. Speaking of which...

What Happened to Space Defense Workers?

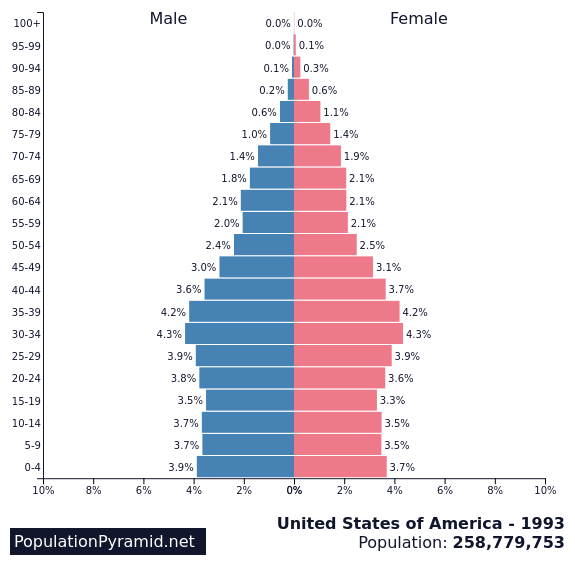

This isn't so much of a mystery. While defense was going through repeated rounds of layoffs, trimming those with less experience or poor performance. A glance at United States demographics in 1993 puts a strong punctuation mark on this.

If you're in your late teens or 20s, are you going to get a job in defense? Not when defense is laying off all of the 20-year olds.

We didn't have high unemployment at the time, however. This begs the question, what industry was hiring?

You guessed it - technology and finance companies.

Aside from required programming coursework, many aerospace engineers also end up programming for sizable fractions of their weekly activities. Those of us old enough remember the 90s as a decade preceding the 'dot com' bubble in which the internet, personal computers, and related software came to widespread public and corporate use. Microsoft, Oracle, and Cisco were the bywords of the day.

I've heard much office scuttlebutt about those laid off from defense work in the 1990s as well as students graduating during the same period. Legend has it they had high rates of transition into technology and finance companies.

In searching for articles or evidence I've come up empty-handed. This could be an interesting topic to read in the future. Instead, in the following section I use university enrollment data to try to estimate human capital production figures.

In my own personal experience as a member of the tail end of Gen X, when I started work in the space industry in the early 2000s there were very few 20- and 30-year-olds. Something like being a kid visiting your confirmed-bachelor uncle.

Human Capital Production in Spacepower

We've discussed how there was a ~12% drop in demographics coinciding with Generation X. There was also a substantial drop in Gen X aerospace students during the same time. Let's see what we can piece together.

According to the Aerospace Department Chairs Association (ADCA) engineering enrollment survey, only 405 Aerospace Engineering PhDs were minted in 2021 in the United States. That might sound like a lot, but with respect to space-related human capital, it's not. In aerospace engineering departments only 10-30% of faculty focus on space-related topics. Applying this proportion to the PhD students they supervise suggests that the United States is producing only 30-90 space-related PhD graduates every year.

I don't think that's enough.

Also, that's now, during the heady days of SpaceX, Artemis, and increasing commercial and government space budgets. Sadly, the ADCA survey only goes back to 1998. The numbers in the late 1990s were lower by a factor of 2-3. Engaging in more back-of-the-envelope math, squinting our eyes, assuming generously that half of these students were interested in astronautics, somewhere between 10-45 space-related PhDs were granted each year during that period in the United States. To make matters worse, many of those students were international, and may have had difficulty obtaining visas and remaining in the United States.

Ever wonder why it's hard to find a senior astrodynamicist Ph.D.? Wonder no longer...

For astronautics-focused B.S. and M.S. degrees in aerospace the 90s annually saw 1,300-2,000 B.S. and 450-700 M.S. degrees granted. Just like Ph.D.s, I don't think this was enough. Also remember that many of these graduates fled to other industries to find work and begin their careers. For comparison, in 1999 the space industry was valued at $125B. Today its valued at ~$500B.

3) What This Means for National Spacepower

A Shallow Bench of Senior Space Professional Talent

Through demographic evidence we've shown that Generation X is smaller than preceding or following generations (Boomers and Millennials) by 12%. We've also identified that layoffs, lack of hiring, and great opportunities in technology companies skimmed much of the Gen X workforce during their university and early career years, denying them to the space and defense industry.

Combined, demographics and the Peace Dividend - both big events by themselves - have hobbled an entire generation's contribution to national spacepower.

"A century of convulsive change leaves huge demographic gouge marks." Todd Gitlin

So, why aren't there many folks working in space between the ages of 45-60 in government, academia, and industry? I've at least given partial answers to this question.

Demography and the Peace Dividend have conspired to make Generation X rarer in the first place, and to lure them elsewhere with jobs and higher-paying prospects.

I expect a thorough rigorous academic investigation of this question would show that Generation X is deeply underrepresented in the space professional workforce.

A Decadal Jump in Leadership

We hear a lot about how the Baby Boomers are retiring. As I write this article more than half already have retired. We have perhaps another 5 years before most remaining Boomers exit the workforce.

What does this mean?

A lot of senior roles and positions will be vacated. There will be comparatively very few senior space professionals to assume those leadership roles.

As an academic it pains me that I'm forced to give more anecdotal evidence here. The department I work in has ~45 faculty. We're one of the biggest departments in the nation. Amongst that faculty, ~20 focus on space-related research. Again, this is the highest fraction in the United States. Amongst those 20, there is only one faculty member between their early 40s and early 60s. The same holds true at most other top-10 aerospace engineering departments.

Perhaps its not a bad thing. Reaching into your organizational ranks to promote the most promising 40-45-year-olds could reinvigorate a lot of organizational cultures. It also means a lot of experience won't be gathered by those individuals before they're promoted.

A Mandate for the Future?

Spacepower is fundamentally dependent on human capital. I'm not the first to observe this - it borders on folk wisdom.

Looking further back, the great seapower theoreticians of the 19th and 20th centuries expressed very similar thoughts. Adm. Alfred Thayer Mahan wrote often about the importance of human capital in Seapower.

"[T]his [...] [is] a difference in what is called staying power, or reserve force, which is even greater than appears on the surface; for a great shipping afloat necessarily employs, besides the crews, a large number of people engaged in the various handicrafts which facilitate the making and repairing of naval material, or following other callings more or less closely connected with the water and with craft of all kinds. Such kindred callings give an undoubted aptitude for the sea from the outset." (pg. 46, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History)

Leaning further upon Mahan's writings from 130+ years ago:

"[I]t may be admitted that a great population following callings related to the sea is, now as formerly, a great element of sea power; that the United States is deficient in that element; and that its foundations can be laid only in a large commerce under her own flag." (pg. 49, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History)

Replace seapower with spacepower above and you're cooking with gas.

Despite the pessimistic outlook of United States national spacepower being hampered over the next decade or two by leaders with (on average) less experience than before, there are bright spots.

First, the people taking the reins over the next decade or so began their careers in the late 1990s and early 2000s. As young workers in the space industry they participated in the early rise of SpaceX. These individuals are not as beholden to the curse of 'heritage;' they do not generally like design, development, and manufacturing cycles that take a decade or more to produce a spacecraft. Either they or their undergraduate friends have already built and launched rockets, small sats, or other (nearly) mass-produced space infrastructure. Furthermore, they entered the workforce in droves, consistent with or above expectations for the generational size difference between Millennials and Generation X.

This trend has continued. Generation Z is flooding the educational system and beginning their working lives contributing meaningfully to space. In my department alone, undergraduate enrollment doubled in less than 5 years. SpaceX, Blue Origin, Artemis, and others are inspiring many young STEM students to pursue careers in space.

Near-term human capital in spacepower may take a minor hit, but I see a lot of constructive disruption and raw potential in the coming decades.

I'm excited.

Summary

I can draw the following conclusions from our trip through history and demographics:

- Demographics and the Peace Dividend conspire to hamper the human capital contribution to national spacepower, at least for the next 10-15 years. Fewer Generation X members and decreased defense / aerospace funding during their early career led many into technology or finance careers.

- Generation X is deeply underrepresented in the space workforce and industry, government, and academic leaders contributing to national spacepower will necessarily be younger and have less experience, on average. This should continue for another 10-15 years.

- Millennials and Generation Z are entering the space workforce in droves and, in all likelihood, may be overrepresented on a national basis. This is a good thing - Mahan's observations on national seapower translate well to space. The surfeit of high-quality Millennial and Gen-Z human capital in space careers bodes well for future Spacepower.

Subscribe to the Newsletter

If you enjoy this content, show your support by subscribing to the free weekly newsletter, which includes the weekly articles as well as additional comments from me. There are great reasons to do so, and subscriptions give me motivation to continue writing these articles! Subscribe today!